Cricket is one of the few things I really miss about life in Australia, and stumbling across the Japan Cricket Association website recently led me down a rabbit hole centered around willow, an integral yet often unremembered part of life in my two countries.

Come down the willow wormhole with me!

Cricket is booming in Japan. Looking at the website, I was surprised to see how much the game of cricket has developed since I was last in touch with it in around 2007 or so. There are associations in every region of the country, 100 senior teams and about 15,000 players. There are three associations in the Kanto region encompassing Tokyo. The boom in the sport’s popularity reflects the greater presence in Japan of people of South Asian origin.

Whack of the willow calls. Google led me to the JCA website because it said that it was a conduit for televising of the ongoing Border-Gavaskar Trophy, the prize at stake for bilateral Test matches between Australia and India, currently the world’s cricketing superpowers, especially the latter, which bankrolls the game.

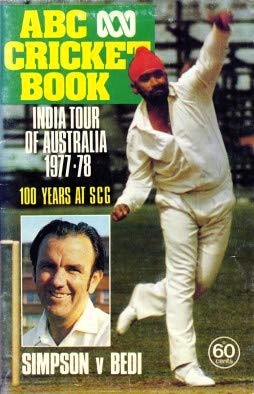

Turning back the clock. I didn’t find the coverage information I was looking for, but the website turned my attention toward India and cricket. This season’s clash is only the second time since the southern summer of 1977-1978 that Australia and India will play a five Test series Down Under. (The other series was in 1991-92). The match-up in the ’70s created one of the fondest, most enduring memories of my youth.

Testa amid testiness. The year 1977 was a tough time. Stagflation ruled, the Sex Pistols were shocking the world the Commonwealth was marking Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, and Australian cricket had ripped itself apart in a battle over TV rights. For the first time, cricket came to Australian audiences through Channel 9, which provided highlights from Australia’s tour of England. The tour started on a high note following the glory of the Centenary Test, but ended in disaster as the Aussies were trounced. The touring party of 17 was divided and in disarray when it was revealed early in the tour that 13 of their number would join World Series Cricket (WSC), a breakaway cricketing group formed by Australian TV magnate Kerry Packer.

Currying favor. Austalian cricket authorities did not expect much of India. Test cricket still ruled the game indisputedly at the time. One-day cricket had made its mark with the first World Cup in 1975, but it was far cry from the colored clothes, white balls, restricted fields and night matches that would make it the most popular form of the sport until that title was usurped by the even shorter, sexier Twenty20 in the early 2000s. India hadn’t played in Australia for a decade at the time, and were not regarded as a power, especially away from home. India had never even won a single Test match in Australia when Bishan Bedi brought his team south. Courtesy demanded the Indians get a go in Australia and the Australian Cricket Board extended an invitation to the team, bracing for a slow season following two bumper summers against England (1974-5) and the West Indies (1975-6) followed by the Centenary Test to offset having to play a Pakistani team that was hardly a drawcard (1976-7). The emergence of WSC made the prospect of an Indian tour even more financially unpalatable. But with none of their players joining the rebels, at least the Indians would be at full strength.

Bringing back Bobby. Cricket wasn’t really professional in 1977. Outside of England, where professionals could play in the County Championship, most elite players also had to work at ordinary jobs while playing. One exception in Australia was Bobby Simpson, then 41-years-old. He was a successful businessman, often with cricket-related enterprises, but also playing regularly at a high level since he had retired as Australian captain, ironically following the aforementioned most recent visit the Indians had made to Australia in 1967-68. Left with a largely youthful player pool, the ACB called on Simpson to come out of retirement and lead the national team. Simpson, whose presentation to cricket authorities with an idea remarkably similar to how WSC would pan out was rejected the previous summer, willingly answered the call.

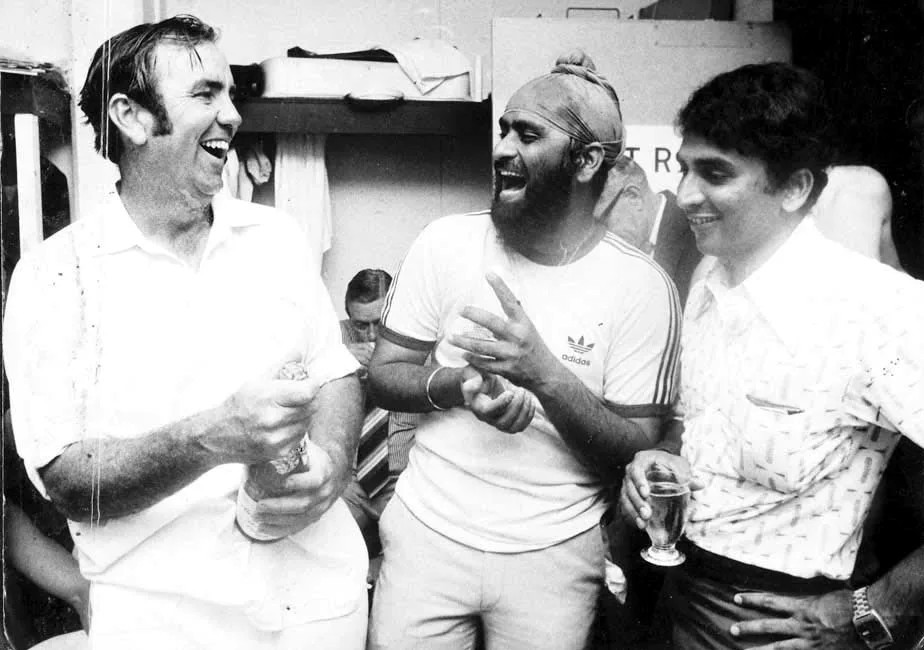

Bish and Bobby. The respective captains of the two teams were long-time friends yet fierce competitors on the field. Their relationship would set the scene for their teams and the series. As the Indians went through a series of tour games against state teams in November 1977, the Australian selectors would be focusing on finding players to join Simpson. Bedi, his spin partners Erapalli Prasanna, Srinivasaraghavan Venkataraghavan, and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar warmed up, while the batting lineup led by the generational talent Sunil Gavaskar and Gundappa Viswanath honed their form as the tourists entered the First Test in Brisbane with a perfect record.

Tearaway Thommo. Australian selectors got a lucky break when Jeff Thomson was made available to the Test team after his WSC contract was overruled by a previous contractual agreement he had made with a Brisbane radio station. Not many players with Test experience would be available, and fewer still would be in form when it came time to pick the team to play the Indians in November 1977. Thommo, probably the world’s best bowler in 1974-1976, would be a boon for the Aussies, even if he wasn’t quite the same player he had been following a freak accident involving an on-field collision with teammate Alan Turner the previous season. (Turner could have claimed a place in the Test team as he didn’t join WSC and was an incumbent national representative, but gave up cricket to sell cigarettes.)

Fancying their chances. India went into the Test series as strong favorites. Their lead-up form was signficant. Australia was led by a 41-year-old at a time when entering the 40s was viewed as a huge step into dotage. And that “old man” would be surrounded by fledgling cricketers whose combined experience did not even add up to Simpson’s key pace bowler Thomson, who had played 22 Tests by that time. Players with Test experience had almost universally failed in the Sheffield Shield and tour games. When the team was picked, six of the 12 would be playing their first game of Test cricket.

The other camp. As the Establishment belligerents readied themselves, the WSC rebels were also about to unleash their talents. These were almost exclusively the world’s best cricketers, had been massively promoted in multimedia form at a time when the concept was unknown and also lured support with the promise of all main circuit games receiving full TV coverage using the then latest technologies and providing face-on footage at all times needed instead of “having to look at a bastman’s arse half the time” as Packer had bemoaned the Australian Broadcasting Corporation‘s cricket filming process being.

Crafting a classic. What followed in the ensuring weeks was one of the most gripping Test cricket series in history. For me, it was a crucial one that fostered a love for the game forever, and a fondness for the Indian team that has endured through to now even though I blame the country for despoiling the game through overexposing 20-20 cricket. I digress, though.

Topsy-turvy. In something of a surprise, Australia would scrape through the first two Tests. Its unexpected 2-0 lead came after narrow victories in Brisbane, and then Perth, where the tourists had them on the ropes at times in both matches. India was not going to give up, though. It crushed the Aussies in Melbourne, the first-ever Indian Test win in Australia, then won even more comprehensively in Sydney. This set up a huge finale for the Australia Day weekend Test in Adelaide.

Wholesale changes. Following two abject performances, for the second time in the series the Aussies would go into the Test with almost half the lineup new to the highest level of the game with four new caps. They also brought back Graham Yallop, who had succeeeded against the West Indies in the triumphant 5-1 win in 1975-6, but never managed to recapture the form needed to get him back into the national team thereafter. The Aussies in the Fifth Test bore little resemblance to the team in thefirst two Tests of the series.

Gripping finale. The closing Test match of the summer was a mirror of the series, with one team seemingly in the ascendency only for the other team to claw its way back into the match. India were assigned a world record target to achieve to win the Test, and the series, and were buoyed by Thommo breaking down with injury leaving the inexperienced Aussie attack with two dependents depleted. Ultimately, on the sixth day of the match and despite a still now record final innings total of 445, the brave Indians fell just short. One of the last wickets to fall went to first-timer Ian Callen, who ran a sports store near my hometown, so I was particularly keen on seeing him succeed. Simmo and his unfancied Aussies had held on, but there was no shame for the tourists, who had given everything and produced the best results in Australia by an Indian team until they were finally surpassed by the 2018-19 squad that recorded India’s first-ever series victory in Australia.

Basking in glory. Against all odds, establishment cricket in Australia had emerged from the India series in seemingly glowing health. The gamble to recall the middle-skipper paid off handsomely, and he ended the series averaging over 50 and led both teams for runs scored. He had marshalled his young troops into an outstanding win over a hardened Indian team that played with flair, aggression and subtlety, notably the batting of Gavaskar and Viswanath and the bowling of Bedi and Chandrasekhar, Most notably, the official Test team had drawn crowds that dwarfed attendances at the flashier WSC Supertests, apparently winning a crucial battle in the cricket war.

Short-lived joy. Australia’s delight would not be a lingering one. Soon after India returned home, Simpson took a team off to the Caribbean on what would be a disastrous tour beset by poor play, injuries, riots, political intrigue and the star find of the Indian summer, Wayne Clark, being under a shadow for “chucking,” essentially a death warrant for a bowler in those days. When Simmo was not given a guarantee for his place in the side against England, he retired again. His vice-captain, Thommo, would play a single game the following season and then stand out of cricket as he wanted to join his mates in WSC. The team leadership was given to Yallop, who led his lambs to the slaughter in a 5-1 loss by what is possibly the worst performance by an Australian team in 150 years of Test cricket. With marketers ramping up promotion of WSC, especially through the cricket anthem, “C’mon Aussie, C’mon,” it was clear that traditional cricket as we had known it in Australia was gone for good. Even my great local hero, Callen, who had performed admirably in that final Test of the magical Indian summer of 1977-78, would never play another Test for Australia.

Demise of Dominance. Australia’s series win would maintain its unbeaten series record against India, but it also spelled the end of that monopoly of victories. In the return series in 1979, India would finally emerge victorious over the Aussies in a series. The teams split three series in the 1980s, including the 1986 matchup that had one of only two Test ties in history. From the 1990s, home team dominance would become the norm. In the Noughties, Australia dominated world cricket and India, home and away, was no exception. But as the 21st century progressed and India re-emerged as an economic superpower, it increased control over the game and has established a stranglehold over the Border-Gavaskar Trophy. A comprehensive win in the First Test of this series suggests that will not change.

Why am I doing this? I’m not sure of the reasons. Only that I remember that amazing few weeks in an idyllic summer of my youth left an indelible mark. And sparked a lifelong interest in Indian cricket. Matches between the two teams are among the most widely anticipated, though India probably ranks wins over Pakistan and England to have greater value than those earned against Australia. For the Aussies used to beating most teams, wins over India have become especially pleasing.

Sunny times. With a bit more thought, I guess the post is sparked by the appearance on Australian telly this week of Gavaskar, who really struck me as a warm and funny bloke. I’d mostly only seen him as a whining run machine beforehand, so I was delighted to see this side of him, and it brought back memories of his wonderful summer, which included centuries in each of the first three Tests, and a sense of gratitude for all the wonderful memories he provided me.

What’s willow got to do with it? Well, willow is used for cricket bats, so that’s a no-brainer. But I initially mentioned that it had a connection with both my countries, Australia and Japan. The Japan reference only came from the karyukai, the world of flowers and willow, which is the name given to the world of geisha, which was one of the things that drew me to Japan in the early years of my time here. Bit of a stretch, I know, but I needed some sort of an excuse to get into this overlong tome.